CHARLES IVES

German Songs

for mezzosoprano and piano

Mezzosoprano

Daniela Aloisi

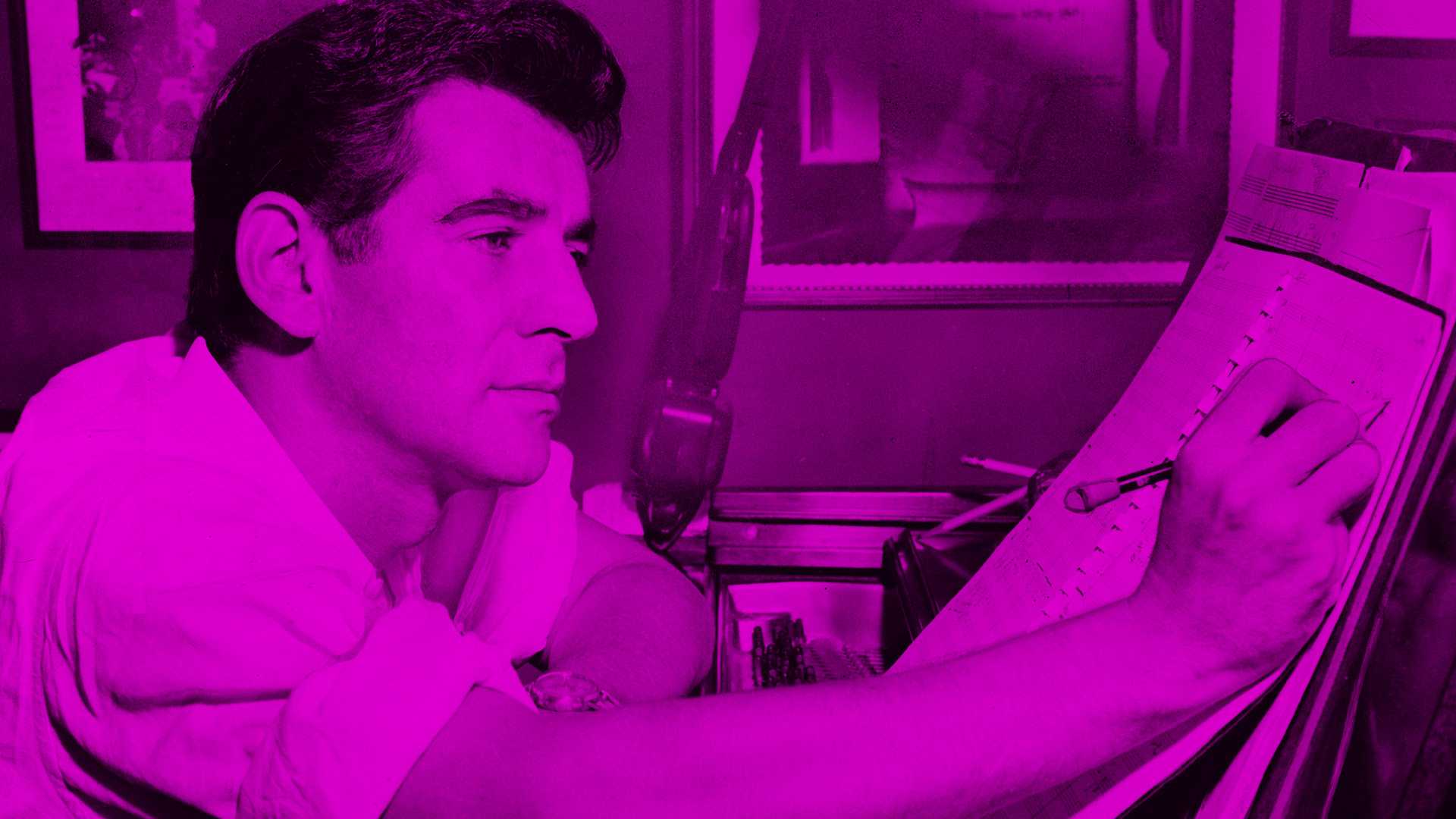

LEONARD BERNSTEIN

I hate music

for soprano and piano

La Bonne Cuisine

for soprano and piano

Two love songs

for soprano and piano

Soprano

Adelaide Minnone

DOMINICK ARGENTO

Miss Manners on Music

Soprano

Eleonora Ronconi

Piano

Claudio Marino Moretti

Charles Ives’ German Songs date from his early period of activity, the 1890s, when the composer was attending Yale University. Not yet established as one of the most interesting voices of the American 20th century, Ives composed just under twenty songs on texts by various German poets, with an already interesting and personal musical writing. The songs were to be published in 1922 in the collection 114 Songs, in the version translated into English. In Weil’ auf mir, du dunkles Auge (Because on me, dark eye), Du alte Mutter (You, old mother), Feldeinsamkeit (Loneliness in the fields), Ich grolle nicht (I hold no grudge), from texts by Nikolaus Lenau, Edmund Lobedanz, Hermann Allmers and Heinrich Heine, the reference to the American tradition and the first tensions towards experimentalism, to which Ives would soon abandon himself, showing a special affinity with the European avant-garde, and contributing to the formation of a new 20th century American tradition, clearly emerge.

Leonard Bernstein’s collections I hate music, La Bonne Cuisine and Two love songs date back to the 1940s, to 1943, 1947 and 1949 respectively. I hate music is a collection of five songs, and bears the subtitle A cycle of five children’s songs for soprano and piano. The texts, written by Bernstein, are light and humorous poems inspired by the world of childhood, in which the author observes reality from a childlike and irreverent point of view. In the brief introductory author’s note, Bernstein writes: ‘In the performance of these songs, shyness must be assiduously avoided. The natural, unforced sweetness of childlike expressions can never be successfully embellished; rather, it will manifest itself through the music in proportion to the dignity and sophisticated understanding of the singer’. With La Bonne Cuisine, four recipes for voice and piano, the composer experiments with writing four songs not on poetic texts, but on four culinary recipes, taken from a French cookbook by Émilie Dumont. The vocal line declaims the different preparations with profound intent, ranging from plum pudding to hare stew, while the piano line accentuates the comic and alienating effect by amplifying the serious declamation mainly through the rhythmic aspect, in a set of references ranging from jazz to film music to contemporary avant-garde. The lyrics of theTwo love songs, Extinguish my eyes and When my soul touches yours, are two poems by Rainer Maria Rilke, taken over by Bernstein in the English translation by Jessie Lemont. Here, too, the composer experiments with the mixing of different styles, but with a more lyrical intent suited to the profound gaze through which the poet Rilke describes the feeling of love.

Miss Manners on Music, by Dominick Argento and with lyrics by Judith Martin, dates back to 1998. The collection, for mezzo-soprano and piano, consists of a prologue and six letters inspired by the pages of newspapers in which readers can write to an expert for answers to various questions. Here the expert is Miss Manners. Readers write to her seeking advice on good manners to adopt in different musical contexts, such as church concerts, contemporary music concerts and evenings at the opera and ballet. The shrewd Miss Manners responds with great appropriateness, only going so far as to confess in the finale that she prefers a lively, easygoing audience to an overly compassionate one (as she imagines herself as the acclaimed star of an opera). Argento’s linear and clean writing picks up on the canon of refinement that the protagonist represents, reaching a parodistic apex of lyrical-dramatic tension – both in the vocal line and in the piano line – precisely in the last two letters, those to which Miss Manners responds by letting herself go in an unexpected confession.

Ludovica Gelpi