WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 5 in A Major K 219

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Symphony No. 1 in C major op. 21

Conductor and soloist

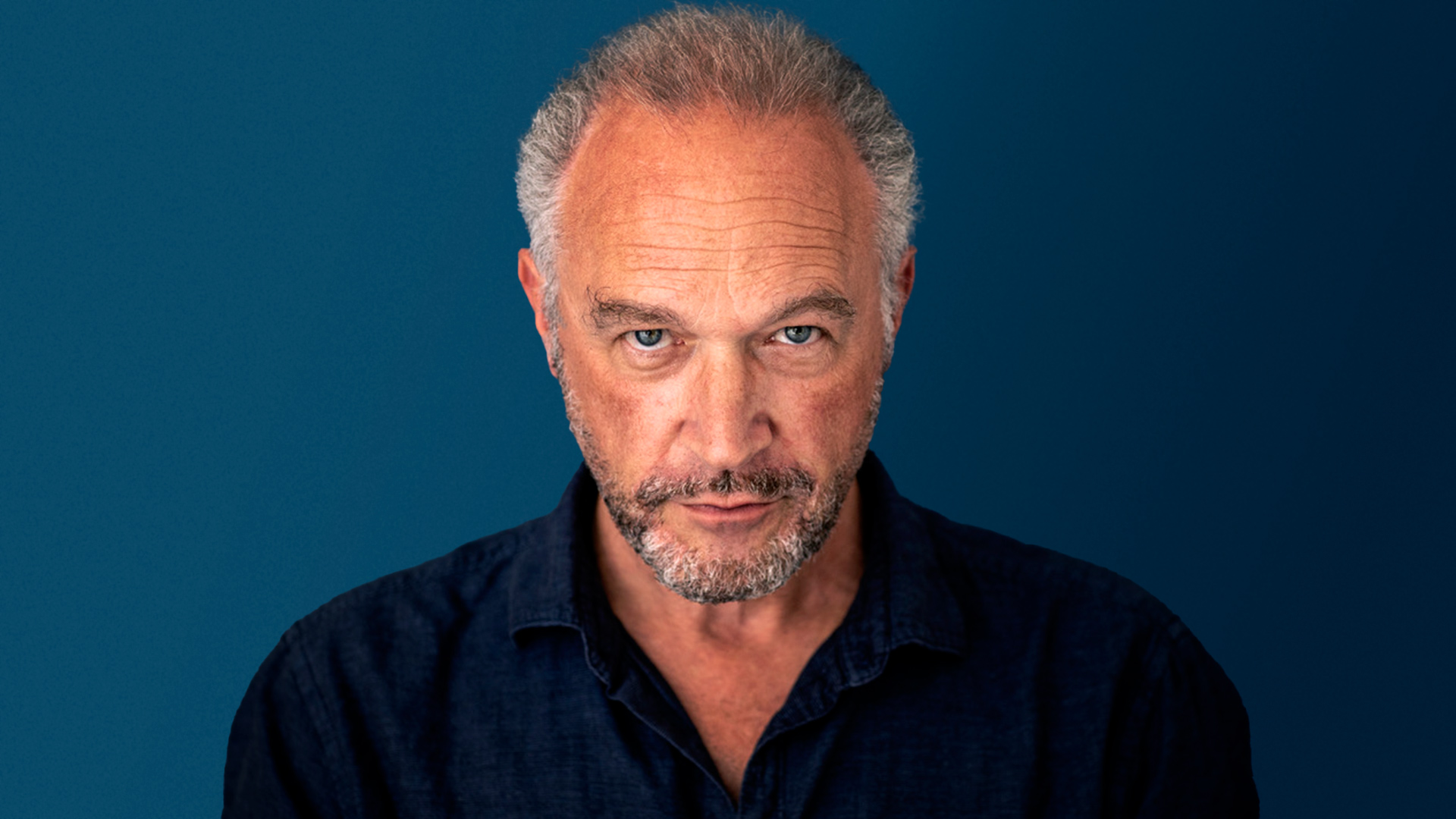

Kolja Blacher

Opera Carlo Felice Genova Orchestra

December 1775 saw Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Concerto No. 5 for Violin and Orchestra in A Major K. 219, which closes the admirable series of Concertos made in the preceding months. This is also said to be the “Türkisch Konzert” because in the concluding tempo there appears a “Turkish-style” episode similar in style and sonority to those in the Rape from the Seraglio and the Piano Sonata K. 332. On the other hand, in those years exoticism inspired by Turkish music was all the rage in the Austro-Hungarian world. The first tempo is an Allegro referred to as “open” precisely to emphasize the directness on the one hand, and the unusual lyrical episode running through it on the other, which some observers believe was intended to be an open homage to the style of his violinist friend Antonio Brunetti. Meditative and restless, on the other hand, is the central Adagio, which precisely because of this “introverted” character was later replaced by a more cantabile Adagio, although in modern times the custom of playing the original slow tempo has properly taken hold. In the concluding Rondo, the “alla turca” episode is all the more notable for the fact that it suddenly interrupts, with its rhythmic and coloristic vivacity, the mannered progression of a traditional eighteenth-century Minuet.

Remnants of the eighteenth-century tradition can still be traced in Ludwig van Beethoven’s first two Symphonies, if the Andante of Symphony No. 1 in C major Op. 21 airs that of Mozart’s Symphony in G minor K. 550, and if the introduction of the Second is exemplified by Haydn’s later symphonic models. The general character of the First, a work from 1800, could undoubtedly recall Haydn if rhythm did not take on a new function in the musical discourse. Rhythm is in fact what sustains, after a slow introduction full of tension with its elusive character, the first theme of the Allegro con brio, elaborated with vigorous and luminous energy, and also the second subject, more melodic and amused but still supported by cadential scans, which help a new dialectic in the development section. In the Andante cantabile con moto Beethoven adopts the sonata-form, and the Mozart model seems evident at least in the opening cue, which is also less endowed with ambiguity; but once again the rhythmic discourse stands out, as in the passage of the insistent timpani pedal. Certainly original, indeed entirely new, is the Minuet, which retains nothing of the eighteenth-century cadenzas, bursting instead aggressively and swiftly like a Scherzo into a vortex of vitality all tinged with chiaroscuro, which barely allows a brief pause in the Trio, played on the contrasting timbres of the woodwinds and strings. The final Allegro molto vivace, prepared by a brief and in its own way eccentric Adagio with its ascending scale (a section of proverbial difficulty for conductors), is in the form of a rondo with an irresistibly lively and playful tone, not without episodes “marked by a somewhat easy joviality,” as Giovanni Carli Ballola has noted.

Enrico Girardi