Opera in three acts by Benjamin Britten

with libretto by Peter Pears,

from William Shakespeare’s comedy

Characters and interpreters:

Oberon

Christopher Ainslie

Tytania

Sydney Mancasola

Puck

Matteo Anselmi

Theseus

Scott Wilde

Hippolyta

Kamelia Kader

Lysander

Peter Kirk

Demetrius

John Chest

Hermia

Hagar Sharvit

Helena

Keri Fuge

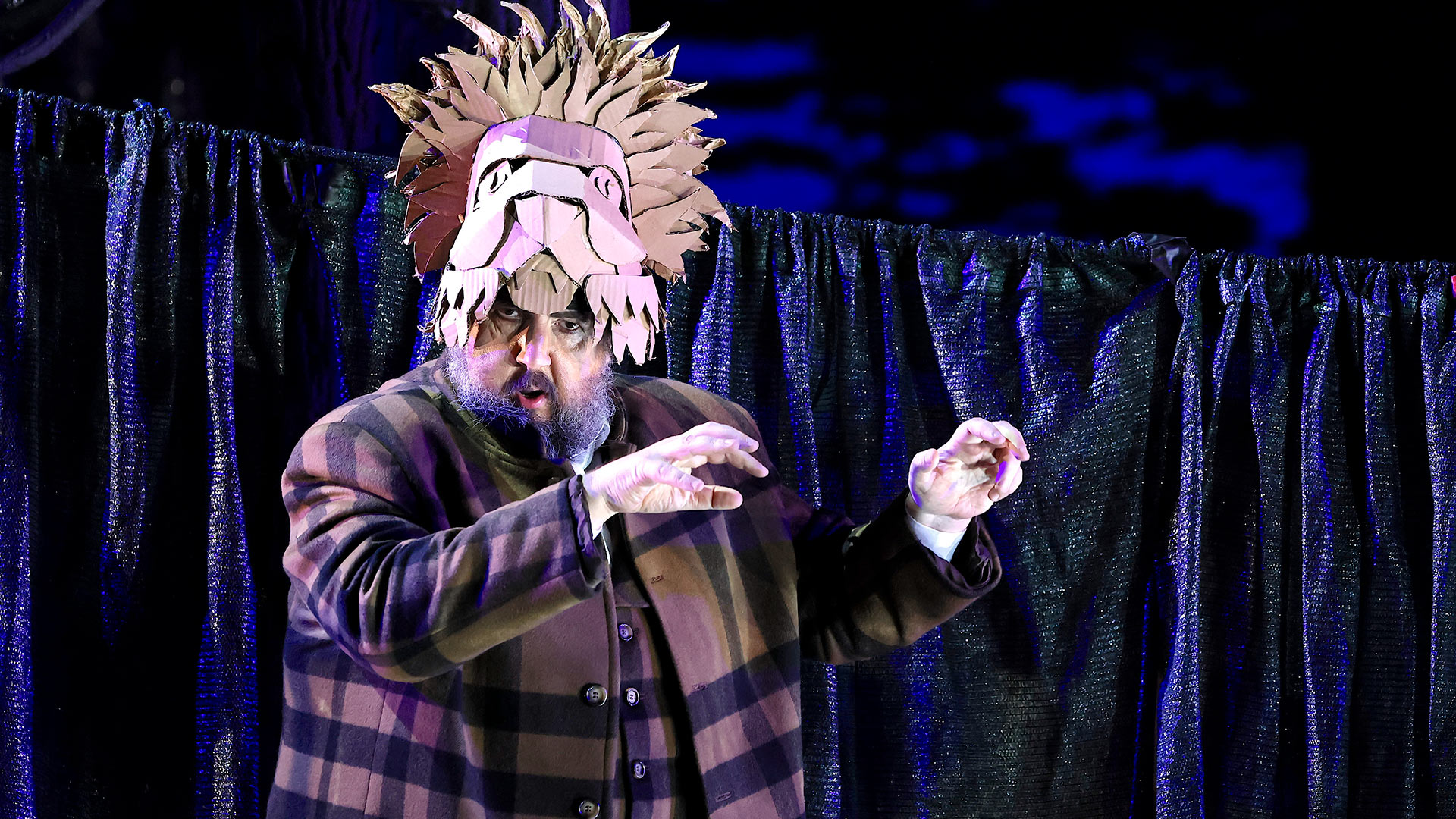

Bottom

David Shipley

Quince

David Ireland

Flute

Seumas Begg

Snug

Sion Goronwy

Snout

Robert Burt

Starveling

Benjamin Bevan

Cobweb

Michela Gorini / Maria Guano (19)

Peasebossom

Sofia Macciò / Leonardo Loi (17)

Mustardseed

Lucilla Romano / Giulia Nastase (19)

Moth

Eliana Uscidda / Denise Colla (17)

Changeling

Francesco Pagliarusco

Acrobat mime

Davide Riminucci

Mimes

Armando De Ceccon, Francesco Tunzi

Conductor and répétiteur

Donato Renzetti

Director

Laurence Dale

Set and costume design

Gary McCann

Choreographer and direction collaborator

Carmine De Amicis

Lighting designer

John Bishop

A new production by Fondazione Teatro Carlo Felice di Genova

in collaboration with Royal Opera House di Muscat (Oman)

Orchestra, Treble choir and Technicians of Opera Carlo Felice

chorusmaster Gino Tanasini

Staging director

Luciano Novelli

Stage musical director

Simone Ori

Répétiteurs

Sirio Restani, Antonella Poli

Stage musical assistants

Andrea Gastaldo, Anna Maria Pascarella

other Choir Master Patrizia Priarone

Lighting Master

Cristina Battistella

Supertitle Master

Simone Giusto

Treble Choirmaster’s Assistant

Enrico Grillotti

Head of musical archives

Simone Brizio

Scenic director

Alessandro Pastorino

Vice scenic director

Sumireko Inui

Consolle supervisor

Andrea Musenich

Stage technicians foreman

Gianni Cois

Tooling foreman

Tiziano Baradel

Audio/video foreman

Walter Ivaldi

Head of tailoring, shoemaking, make-up and wigs

Elena Pirino

Director’s assistant

Matteo Anselmi

Costume assistant

Gabriella Ingram

Scene Assistant

Eleonora Peronetti

Make-up and hair co-ordinator

Raul Ivaldi

Scenes, costumes, props and footwear

Fondazione Teatro Carlo Felice

Wigs

Mario Audello

Supertitles

Enrica Apparuti

Opera in brief

by Ludovica Gelpi

In August 1959, Benjamin Britten decided to compose an opera that could be staged within the following June, on the occasion of the Aldeburgh Jubilee Hall reopening – home of the renowned festival founded by the composer in 1948. The choice of the Shakespearian subject was due to the composer’s passion for Shakespeare’s work as well as to the possibility of adapting the theatrical text into an opera libretto. The work of adaptation happened in collaboration with the partner Peter Pears with the aim of maintaining quite precisely the original work, with minor changes to render the plot more fluent. Despite a modest reception at first, A Midsummer Night’s Dream is now considered one of the best operas by Britten.

In the comedy transposition, the composer takes full advantage of the dramaturgic potential of the Shakespearean subject by highlighting the three narrative layers (the fairy realm, the young Athenian lovers, the group of artisans and aspiring actors) as well as by amplifying the element unifying the three layers. the oneiric and fantastic atmosphere of a midsummer night. This very atmosphere – the heart of the charm of Shakespeare’s piece – is here effectively recreated with intensity thanks to the music. In Britten’s writing, always very personal and experimental (especially at a timbre level), many references to the story of the opera are embedded. Such a choice originates from the desire to underline the elements that the theatrical text has in common with the most beloved operistic plots. It almost represents a tribute to the history of the opera, developing on a dramaturgic as much as on a musical level. This way, Britten seconds a tendency towards the late-1900s encyclopedism. Among the strategies the composer employs, we can find a special attention to vocal registers. The use of treble voices for the group of fairies immediatly ignites the listeners’ fantasy, projecting the audience in the fantastic dimension of the story; for the same reason, Britten chooses the unusual register of the countertenor for one of the male protagonists, Oberon, vocally connoting himself as the King of fairies. Many popular and ironic references, almost parodies, are present in the sections dedicated to the artisans, whom instead represent a more realistic dimension, particularly a parody of Lucia di Lammermoor in the meta-theatrical section of the third act. The same perspective applies to the writing of a pathetic sentiment at times expressed in Titania’s interventions. Such a figure is inspired by the most beloved heroines of melodrama’s history.

Benedetto Croce wrote on the Dream: «the rapid ignitions, the incostintent frequencies, the whims, the delusions and and disappointments, the many kinds of love folly are here embodied and weave such a vivid and real world such as the one of the men visiting their beloved ones, giving them enrapturing and tormenting feelings, both uplifting and and lowering them; since everything is equally real and fantastic, depending on how one wishes to call it. The sense of dream, of a dream-reality, remains and blocks any cold allegory or apologue». Shakespeare’s reading of Britten’s work focuses such a clash-union between the fantastic and the real as a central element of the whole narration. The expressive variety of Britten’s writing aims at describing musically the two dimensions – with all their different facets – and the ways in which the interact with each other. Because of such a focus on the mysterious coexisting of the real and the fantastic, the same expressive variety describing them is presented as compact and coherent.