Tragic melodrama in three acts by

Giuseppe Verdi

with libretto by Francesco Maria Piave,

from the short poem by George Byron

Characters and interpreters:

Corrado

Francesco Meli

Medora

Irina Lungu

Seid

Mario Cassi

Gulnara

Olga Maslova

Selimo

Saverio Fiore

Giovanni

Adriano Gramigni

A eunuch

Giuliano Petouchoff

A slave

Matteo Michi

Conductor

and orchestrator

Renato Palumbo

Director

Lamberto Puggelli

Set designer

Marco Capuana

Costume designer

Vera Marzot

Weapons master

Renzo Musumeci Greco

Lighting design

Maurizio Montobbio

Director’s assistant

Pier Paolo Zoni

Set up by the

Fondazione Teatro Carlo Felice di Genova

in co-production with the

Teatro Regio di Parma

Orchestra, choir and technicians of Opera Carlo Felice

Claudio Marino Moretti, choirsmaster

Staging director

Luciano Novelli

Stage musical director

Andrea Solinas

Répétiteurs

Sirio Restani, Antonella Poli

Stage musical assistants

Andrea Gastaldo, Anna Maria Pascarella

other Choir Master

Patrizia Priarone

Lighting Master

Silvia Gasperini

Supertitle Master

Simone Giusto

Head of musical archives

Simone Brizio

Scenic director

Alessandro Pastorino

Vice scenic director

Sumireko Inui

Consolle supervisor

Andrea Musenich

Stage technicians foreman

Gianni Cois

Chief electrician/lighting booth

Marco Gerli

Tooling foreman

Tiziano Baradel

Audio/video foreman

Walter Ivaldi

Head of tailoring, shoemaking, make-up and wigs

Elena Pirino

Make-up and hair co-ordinator

Raul Ivaldi

Scenes, costumes and props

Fondazione Teatro Carlo Felice

Fondazione Teatro Regio di Parma

Equipment

E. Rancati

Footwear

Epoca

Surtitles by

Enrica Apparuti

Opera in brief

by Ludovica Gelpi

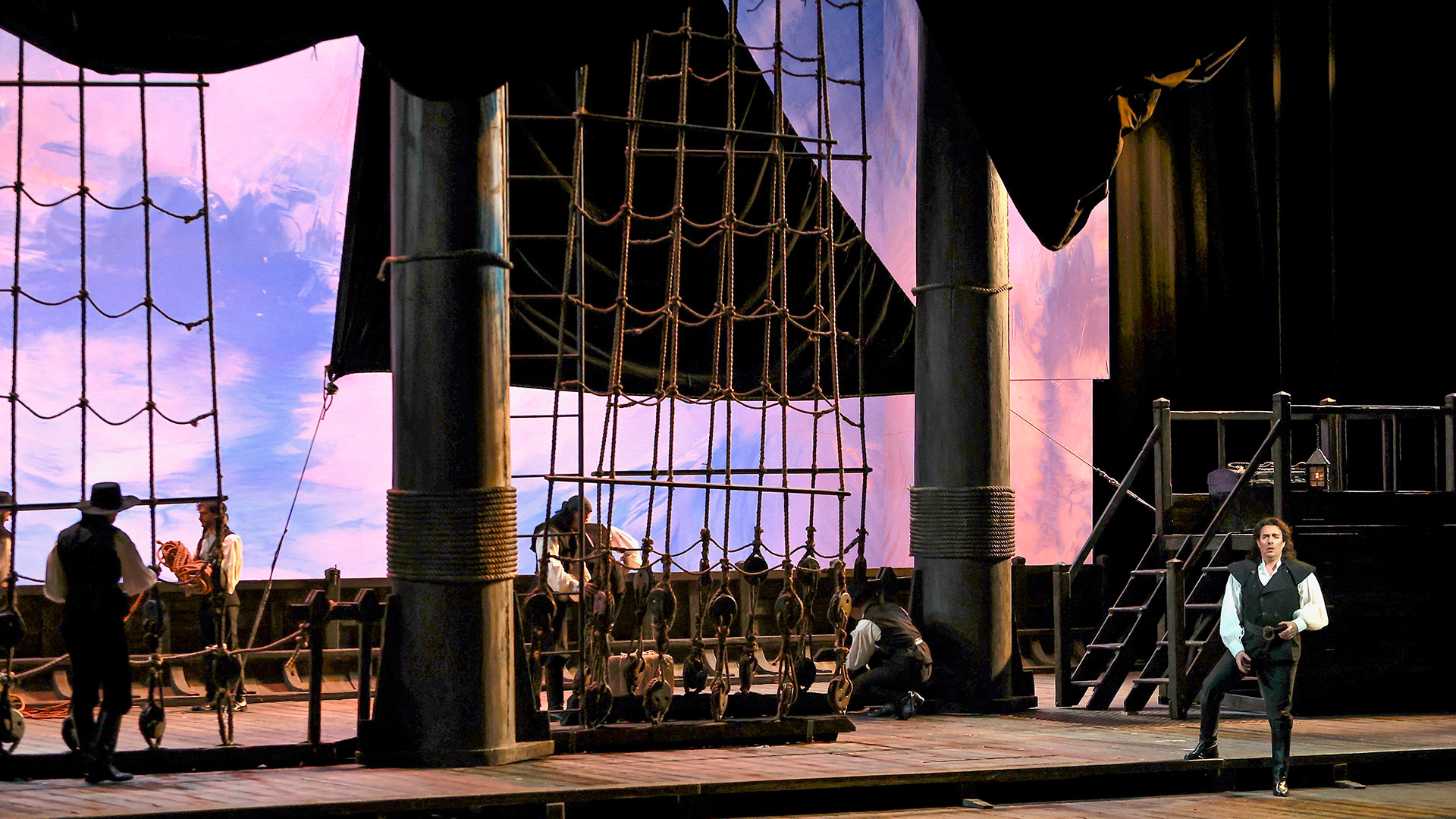

Verdi composed Il corsaro in a period of very intense activity, only a few months after the previous work, Macbeth, and the following one, Luisa Miller: these were his ‘jail years’. The composer was in Paris and in the winter between 1847 and 1848, having to fulfil a delivery to the publisher Francesco Lucca, he devoted himself to the production of this tragic melodrama in three acts, although he was still unclear when and if the opera would be performed. The subject, the eponymous poem by George Byron, had caught Verdi’s attention in 1844, so much so that he had already entrusted the reduction to an opera libretto to Francesco Maria Piave. The story traces the adventures of a group of corsairs, including the protagonist Conrad, his beloved Medora, and also the pasha Seid with his Muslim soldiers, his odalisques and the beloved Gulnara. The characters live amidst overwhelming love, battles and intrepid adventures at sea. It is an affair in full romantic spirit, very much akin to the Milanese and Parisian cultural circles frequented by Verdi. Despite the initial impetus, and perhaps also due to the frenzy of that professional period, the composer did not take much interest in the fate of his creation, so much so that he did not attend the first performance, on 25 October 1848 at the Teatro Grande in Trieste. The Corsaro‘s fortunes were poor, after the first performances the opera was not performed again until 1963, and to this day it is one of Verdi’s least frequently performed operatic works.

The dramaturgy is sometimes noted as a weak point of the play, yet the characters are well characterised and find their proper place in a cohesive and concise action. The protagonist has a mysterious past: we do not know why Corrado, a man with a strong sense of honour and capable of sincere feelings, has ‘converted’ to a life as a mercenary, made up of fights and violence. The complexity of his character, a true romantic hero full of contrasts, is effectively rendered throughout the play. Medora, for her part, has less space on stage than the other co-protagonists, but it is enough for her tormented love to be portrayed with rare intensity. Seid himself, a pure antagonist, is not lacking in fascinating nuances: the pasha moves from cruelty and ruthlessness towards his enemies and in particular Conrad, to vulnerability in the face of his beloved Gulnara – whom he also holds prisoner and considers a possession of his own. Gulnara, the other woman, the one who for Corrado can never be Medora, is a character of enormous romantic strength: despite an ungrateful fate, which has made her first a prisoner of Seid’s sick love and then of her own, unrequited love for Corrado, the young woman fights for her ideal of freedom, for which she is ready to become an assassin and risk her own life. The singularly varied choral dimension takes shape amidst the mysterious exoticism of the pasha’s odalisques, amidst the heartfelt heartfelt heartfeltness of Medora’s handmaids, and is inflamed in the battle scenes, as much between Conrad’s wild corsairs as between Seid’s resolute Muslim soldiers and dukes. The last scene, almost an open ending, brings together the main traits of each character, leaving the viewer to choose whether Conrad will go to his death torn by grief, finally succumbing to the depths of his evil, or whether he will be saved by his corsair companions, until perhaps one day he will be able to love Gulnara as he loved Medora.

Verdi’s music offers passages of great lyricism and dramatic intensity in the exaltation of the moments of greatest pathos, but also cohesion and fluency in the scenes of relaxation. There is no lack of references to the Italian tradition of the first half of the 19th century, the solid awareness acquired in the 1940s, but one perceives the desire for an evolution in both musical writing and formal structure. With Il corsaro Verdi prepared to close his ‘first period’ in search of new ideas, to arrive at those highly personal insights that would soon consecrate him with his famous Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata and would definitively change the history of melodrama with the experimental works of his maturity.